people with common cultural traditions and shared descent

The people of the Williams River Valley are homogenous even by the standards of rural Australia. It was early settled by the usual mix of British and Irish peoples and as throughout Australia, these ethnic differences were largely played out along religious lines. Scots Presbyterians, both directly from Scotland and indirectly from Ireland, were a slightly more prominent grouping than in many other places. Irish Catholics, both ex-convicts and assisted migrants were also numerous, but formed distinct communities only at Brookfield and Summer Hill. Aside from the usual English, the Welsh had a distinctive impact early on through a number of individuals who named and settled on the Allyn River around Gresford, with other Welsh settlers such as John and Sarah Edwards settling at Salisbury.[1] While the English majority was Anglican dominated, numerous dissenters also resulted in Congregational and Methodist communities, particularly around Eccleston and Salisbury further up the Allyn and Williams Rivers.

Perhaps most distinctive among the groups from the British Isles were poorer Gaelic speaking Scots Presbyterians who at first settled near Paterson and later moved to the Gloucester area. While at Paterson, the Presbyterian School advertised in 1848 that: ‘Preference will be given to one who can speak and teach the Gaelic language grammatically’.[2] These Scots were ‘Free Church’, and later this Barrington River community of ‘Scotch’ whose ‘elder folk spoke Gaelic almost exclusively’, preferred to welcome a Wesleyan minister to any representing the Presbyterian Church of NSW, even contributing to his ‘stipend’.[3]

While most ‘free setters’ came from various parts of the British Isles, many in fact come from other parts of the world than is usually realised. This fact is often obscured by the tendency for those with non-British names in the early settler period to change them so as to better fit in or to give their children a better chance of getting ahead in the xenophobic culture that dominated. Two of the earliest ship builders to operate at Clarence Town, Francis Roderick and Andrew Smith, for example, were both Portuguese, and were originally named Francisco Rodrigues and Andre Femeria.[4] Another such was Andrew (Andreas) Rumbel from one of the German states, whose many descendents still populate the district. A cooper, Andrew Rumbel’s skills in making barrels for carting water and salting beef were of much value locally.[5]

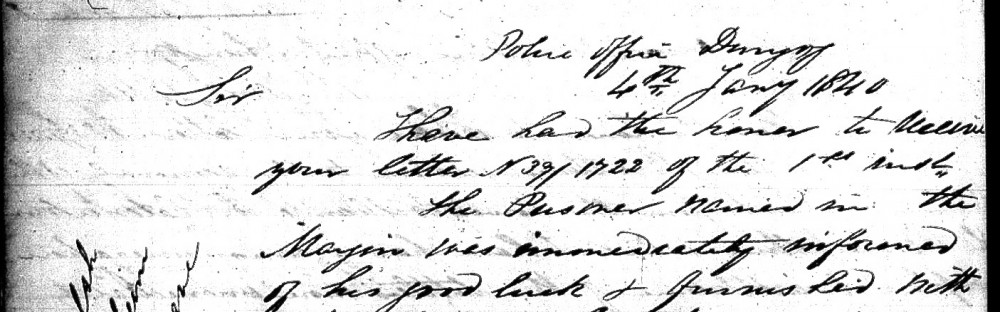

With the ending of transportation in 1840 the Australian Immigration Association was formed to find cheap labour after the ending of transportation, including Indian coolie labour.[6] However such proposals were resisted and only one Dungog landowner is known to have actually brought in ‘coolie’ labour. John Lord is reported to have had 17 Indian coolies plus a ‘Sindar’ (overseer) on his Williams River estate in 1841.[7]

The nearby Australian Agricultural Company also employed many Chinese people from Amoy (Fujian) on contracts as shepherds and while a few of these did remain and settle in Australia, none are evident in the Williams Valley. A few Chinese market gardeners did settle in the three valleys later, one winning prizes at the Dungog Agricultural Show, but these can be assumed to have been Cantonese people arriving in the post-gold rush period.[8] In Paterson a group supplied the town with vegetables in the 1880s, and from Dungog in 1883 it was reported that: ‘We have two parties of Chinamen cultivators in the suburbs; in consequence, vegetables are plentiful and cheap.’[9]

Market gardens and at least one a fruit & vegetable store were operated by Chinese people at Clarence Town. When one brought a wife, the rarity excited the locals:

We now can boast of a real live Chinese lady resident. One of our Chinese gardeners, Ah Young, has taken unto himself a wife, one brought out from China. There was quite a gathering at the wharf yesterday to witness the arrival of the pair.[10]

Wine production was an early interest of landowners in the Colony and this led to the search for non-British immigrants in the form mainly of Germans with vine growing skills. At one point, with transportation ended and the gold rushes more attractive, agents organised this migration and a bounty scheme assisted those with the skills to make the journey.[11] In 1847, following the government’s announcement of a bounty on eligible immigrants such as vinedressers, Wilhelm Kirchner advertised himself as an immigration agent to the landowners of the Hunter Valley. It was reported that: ‘He [Kirchner] considers that vinedressers could be obtained at £15 per annum, and wine coopers at £20.’[12] By September Kirchner had obtained orders for 43 families from the landowners of the Hunter.[13] While Kirchner does not appear to have travelled to Dungog he did visit both Paterson and Maitland.[14] A list of landowners interested in Kirchner obtaining migrants with vine related skills does not appear to include any from the Williams or Allyn River valleys; the Hunter however is represented.[15]

The first of these German families arrived in the Hunter area (including to vineyards on the Allyn river), in 1849, on conditions that bound them to work off their passages with their contacted employees for at least two years. Once this was done, many moved on to other employment or to their own farms and it is at this point that many began to enter the Williams River valley and the countryside surrounding Dungog as well. Jakob Hofman, for example, obtained property at Brookfield, while at least one couple, began at Brookfield before moving nearer to Newcastle. Another such immigrant was Jakob Paff and his wife Christina and their four children, who worked on the Paterson River before purchasing 80 acres also at Brookfield in 1861. Brookfield was a very Catholic area of Dungog with many tenant farmers of Irish descent. Most of the Germans who arrived in this assisted migration of the early 1850s were also Catholic, though this did not necessarily mean the two groups got on well together.[16]

John and Mary Trappel arrived from Germany in 1852 and worked for a time at Campsie, an estate between Vacy and Gresford. Their daughter died age 5 and was buried in the Catholic cemetery at Summer Hill. In 1866, John Trappel, under the 1861 Land Acts, was able to select 40 acres at Wallaroo Creek (Woerden).[17] Joseph and Lenna Eyb were also German immigrants who arrived in Australia in 1853, subsequently moving into the Big Creek area of Wallarobba. Joseph Eyb was naturalized in 1865 and selected 40 acres at Big Creek (Hilldale after 1905), at the head of Mirar Creek.[18]

In the 1870s, another influx of German settlers attempted to revive wheat growing, though without success.[19] The growing of vegetables was also undertaken with the crown of Mt Douglas [Gardener’s Road] occupied by a fine orchard and vegetable garden which supplied Maitland, Dungog and Paterson. This area from Mt Douglas to Clarence Town was reported to be poor land, well worked by German settlers.[20] Clarence Town itself also has a number of families of German decent.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Williams Valley district appears to have had a number of itinerant hawkers from India. They would travel to isolated farms with goods for sale and perhaps make purchases of eggs or chickens. Little is known of these men, but they may have used Dungog town as a base at one point:

‘It appears that the Indian Hawkers in this district are doing a big “biz”. They are building a new place on their lot in Lord Street. When this is erected there will be a veritable colony of Hindoos.’[21]

Aside from these modest groups, individual men and families from various locations have also come to the Williams River Valley. The Capararo family originated from Capararo in northern Italy with Antonio Capararo’s arrival in the early 1880s. After marrying, he purchased a property at Carrabolla in the Upper Paterson Valley. His attempt to grow grapes this far up the Paterson was not successful, though his oranges were more so.[22] Another addition to this limited ethnic diversity was the arrival of Tony & Jack Barbouttis from Castellorizo, Greece, about 1922. The Barbouttis family for a generation settled in Dungog and ran a number of successful cafes, including one on Dungog railway station before moving to Newcastle.[23]

Culturally the impact of any one of these ethnic groups outside the Anglo-Irish has been slight or non-existent and the Williams Valley remains a mix of Anglo-Irish descended Australians with only slight recent additions of urban migrants from wider ethnic backgrounds and a handful of new arrivals directly from overseas.

- Davies, Salisbury Public School, p.7.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 4/3/1848, p.1.↵

- Uniting Church, Dungog, Gateway to the forests and faith, p.15. See 8.2 Religion, for details of the dispute between the two Presbyterian groups.↵

- Murray, Colonial Shipwrights of the Williams and Paterson Rivers, Chapter 1 (n.p.).↵

- Rumbel, The Rumbel Family Tree, p.1.↵

- Sullivan, Charles Boydell, p.76, Australian, 12/12/1840, p.1.↵

- Sydney Herald, 4/10/1841, p.1S. (Later people, generally referred to as ‘Hindoos’, frequently operated as itinerant peddlers in the Dungog district but no link between these two groups is evident.)↵

- Williams, Chinese Settlement in NSW, p.4 & Maitland Mercury, 16/4/1887, p.7.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 2/8/1890, p.6S & 13/1/1883, p.2S.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 21/6/1887, p.3.↵

- Cloos & Tampke, German Emigration to NSW 1838-1858, p.viii & 7.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 30/6/1847, p.2.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 8/9/1847, p.2.↵

- Maitland Mercury, 18/8/1847, p.1.↵

- Cloos & Tampke, German Emigration to NSW 1838-1858, Table 2, pp.8-9.↵

- Cloos & Tampke, German Emigration to NSW 1838-1858, pp.27-31, p.160 & p.170.↵

- Trappel, The Trappel Story, p.25 & p.42.↵

- Sippel, Hilldale Union Church 1899-1999, p.6.↵

- Hunter, Wade’s Corn Flour Mill, p.26.↵

- Gow, Kempsey to Dungog, p.84.↵

- Dungog Chronicle, 23/9/1902.↵

- Capararo, Looking Back, pp.10-11.↵

- Williams, Ah Dungog, p.37.↵