marking the consequences of natural and cultural occurrences

It is known that Gringai people, as did other Aboriginal peoples, celebrated certain events. The exact nature of most of these is unknown today but at least one concerned a natural occurrence, in the form of a comet, which initiated a special gathering and ceremonies related this.1

For the European settlers, their Christian religion in its various denominations was of great significance, and regular celebrations on Sundays and specific feast days were the foremost events on the calendar. Religious holidays such as Christmas predominated, but as time went on more secular ones, such as Empire Day and Coronation Day were also celebrated; usually with picnics, speeches, dinners and, in later times, dances. In 1861, for example, as part of the New Year celebrations, a ‘balloon’ was sent up from Finch’s Royal Hotel at Dungog.2

Little is known about what arrangements a town might make to mark Christmas, but an account of one resident’s disappointment at the appearance of Paterson at Christmas 1866 gives an indication both of what this town did (or didn’t) do and what others presumably did.

Taking a stroll through our town this evening (Christmas eve) we could see nothing to indicate that this festive season had arrived, which in every other town is generally commemorated by a grand display from the butchers’ shops, the green grocer, the public houses, and other places of business. … only one little shop in the town presented anything like a Christmas appearance, with its green bushes and lighted appearance, sufficient to attract anything like a number of customers. We must say our town this evening presented anything but like a Christmas eve appearance, but rather a very dull, unanimated, and unbusiness character.3

A few years later in 1872, Paterson still seems reluctant to get into a Christmas spirit, but it does seem to be attracting people who are out for a holiday drive:

The Christmas festival has passed over extremely quiet. No public amusements were got up and the holiday has passed over chiefly in the meeting of distant friends, and in a convivial manner amongst acquaintances. We have noticed that many Maitland, residents have driven out in their various vehicles, and much enlivened our streets daily throughout the holidays. A drive out to our little village seems to be a very favourite pastime for our Maitland friends. What a pity there is not a little spirit amongst the Patersonians, that they cannot arrange some little diversion at holiday times, to entertain our visitors on such occasions. We should think they would be amply repaid for their trouble if they would only attempt the movement.4

In addition to celebrating specific holidays, many celebrations and entertainments were organised around local events, such as the laying of foundation stones and the official openings of buildings, marked with speeches and dinners. These ceremonies were often also fundraising exercises for the costs of the associated building. The opening of a new bridge, or in a later period, a tennis court, and many other openings would also be marked by speeches, dinners, and often balls.

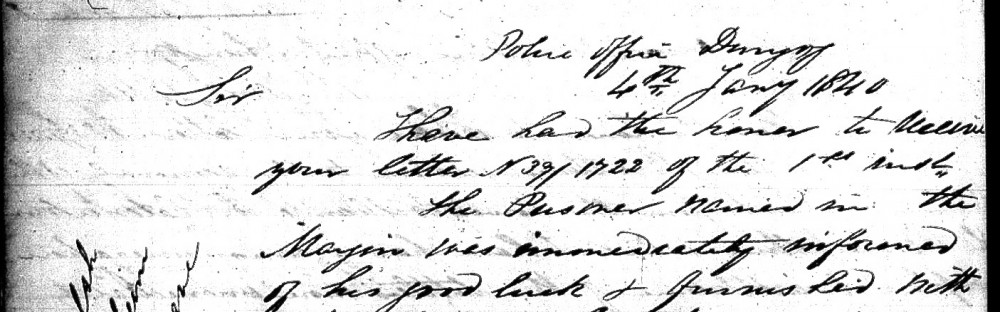

Also common in the 19th century was the raising of funds to mark the leaving of people from certain positions or from the district. A ‘purse’ would be raised via subscriptions; the subscribers of which would be listed in the newspapers along with a letter of thanks from the receivers.5 In latter times such events were most often held for departing ministers, with a dance at the associated church or parish hall. At Christmas, when the nuns from the St Joseph’s Convent at Dungog would return for a time to their main convent at Lochinvar, the local community would raise money for a Christmas present.

As well as a purse, the farewelling of a long-term resident, such as a minister, shopkeeper, magistrate or doctor, was also a cause for a gathering, and the detailed account of such a farewell of Dr Wigan from Clarence Town in 1856, gives an indication of how these events were organised generally. Dr Wigan was invited to a ‘public dinner’ by his ‘friends and patients’ who wished to ‘show him some token of the high esteem and regard in which he was held in the district of the Williams River’. Held in a marquee set up at Clarence Town’s George and Dragon Inn, the numbers attending are not certain, but the writer assures us they included most of the ‘respectable inhabitants and settlers’. As was usual with these public dinners, a chair was appointed to handle the large number of speeches that were an essential part of the event. For his occasion ‘Thomas Cook, Esq., J.P.’, was chair, and ‘Thomas Holmes, Esq, J.P.’, was vice-chair.

The whole event began at five o’clock with the eating of the ‘good things provided for them’ until the ‘removal of the cloth’. It was at this point that the toasts and speeches began. The health of The Queen, Prince Albert, and The Governor and Lady preceded ‘the toast of the evening’ to Dr Wigan, by the chair, followed by a prepared address by the vice-chair, all praising the good doctor and much regretting his departure. After nine ‘vociferous cheers, and ‘one cheer more’, Dr. Wigan gave a speech in reply.

After this, the health of a number of either categories of people or causes was drunk, to which various representatives responded. These included ‘The Members for Durham’, ‘The Clergy’, ‘Prosperity to Clarence Town’, ‘prosperity to the educational interests of the colony’, and finally to the ‘health of the Chairman’ and ‘Vice-Chairman’. But not quite finally, as Dr Wigan then proposed ‘the health of Mr. Dark, his wife, and family’ which was replied to in a manner that ‘caused a great deal of laughter’. This was followed by ‘the health of the ladies’ and ‘the health of the host and hostess’, and then by the true marker of the end of such an occasion, the vacating of the Chair and the voting of thanks to the Chair.6

In case it is assumed that such events were all good cheer and heartiness – certainly the impression the Maitland Mercury writer wished to convey when he merely described the response of ‘W. M. Arnold, Esq., M.P.,’ as ‘a speech of some length’ – an alternative account of this event exists in the Empire. Here, in this not so local paper, we find that Mr Arnold gave a very spirited defence of his election campaign, so spirited, that he was shouted at to sit down and the Chair threatened to leave if order was not restored. Mr Arnold insisted on calling some of his detractors ‘geese’ before order was restored and, according to this writer, the conviviality continued.7

The habit of marking an event with speeches certainly continued, and in 1895 when the Governor of NSW came to Dungog to open the Dungog Cottage Hospital the event was marked with a parade, bunting, a floral arch, many speeches, a tour of Wade’s Cornflour Mill, the foundation laying itself, and a special dinner with more speeches. The opening of the railway to Dungog in 1911 was similarly celebrated with a floral arch, many speeches and a dinner.

In 1907 the ending of a period of dry weather was marked with religious services:

November 27 was observed as a day of thanksgiving for the splendid rains, which have fallen in the Dungog, Stroud, and Clarencetown districts, the day being strictly observed, and the public services largely attended.8

The many deaths resulting from the First World War led to the holding of annual Anzac Day marches and services, as well as numerous honour boards and memorials. The Memorial Town Hall at Dungog was built in 1920 and Honour Boards were often erected to fallen members in Churches, Masonic halls, schools and at community halls. Some Honour Boards have outliving the buildings in which they were first erected and are now located in local history museums.9

The dedication of the Honour Roll in St John’s Church, Vacy in 1918 was one of many:

The occasion was the important one of the dedication of an honour roll recently erected in the Church by the parishioners in memory of the men who have …. made the supreme sacrifice. The board, which cost £21, measures about six feet x two feet, is of polished cedar beautifully carved, is from Red Cross industries, Sydney, and is the work of returned soldiers. … the wife of the senior churchwarden … unveiled the tablet, which was covered with the Union Jack … At the close of the service the congregation adjourned to the local School of Arts, where a reception was given … and while refreshments were being partaken of, kindly provided by the ladies, short speeches were delivered … A few musical items and recitations were given and a most enjoyable evening was brought to a close with the signing of the National anthem.10

In the years after the First World War it became common to mark an event with dancing, which was also often a fundraising event. Sometimes this dance became an event in itself, such as the annual Diggers’ Ball which began as a fundraiser to assistance to the many ex-diggers who were passing through Dungog. This Diggers’ Ball is still held each year as a Diggers’ Dinner at the Dungog RSL. In 1930, when the James Theatre was newly renovated and re-opened, the official opening was held at the Diggers’ Ball and a ribbon cut ‘in true Diggers’ style’ by the Mayoress.11

The role of the local Major and Mayoress in opening the many events that took place – Catholic and Anglican Bazaars, Scottish Balls, Flower Shows, etc. – was a prominent one. For Debutante Balls, which from the 1940s to the 1960s marked the ‘coming out’ of young girls, it was also common to invite the Mayor of Newcastle or other such dignitary to present the debutante to. In Gresford, debutante balls continued to be held at the School of Arts until the 1990s.12

In the middle of the 20th century began a series of centenary occasions as various towns, schools, halls and churches reached their 100th and even 150th years. These too were marked with celebrations, often involving commemorations in which locals, often descendants of the original participants, would dress in period costume and recreate the first opening. In addition, local teachers and others would write up histories of the school or town being celebrated, often speaking to older community members in order to preserve what people began to realise was a fast fading community memory. These centenary and sesquicentenary celebrations have included the 100th of Municipal Government, the 150th of Dungog, and most recently the 100th of the railway coming to Dungog.

The various Churches have also celebrated their centenaries and sesquicentenaries with commemorative booklets. The Catholic community at Dungog is unusual in that it has changed its church’s location twice in its history, and so in the 1970s its commemoration included a pilgrimage to the site of the first Catholic chapel at Sunville. A cairn of bricks from this first Church was erected outside the current St Mary’s Church, just as a stained glass window of this Church commemorates the Fitzgerald family who donated the land for this first Church.

Many parks were dedicated as memorials in the 1960s and 1970s, often by the new service clubs such as Lions or Apex. One such was the Dave Sands Memorial, erected in 1972 to mark the place where promising boxer Dave Sands died in a motor accident in 1952. This memorial was put in place in response to the number of people coming to Dungog asking after the place of his accident. The dedication ceremony at the park (located 15kms north of Dungog town), was accompanied that night by a series of boxing matches held at the James Theatre, and refereed by Leo Darcy, brother of Les Darcy.

In the 1950s, there began a number of events to mark life in the valley generally and also to help attract more visitors. These events evolved and have had many names, such as the Williams Valley Festival and Tall Timbers Festival. Most recently Dungog has held an annual Pedalfest, the Thunderbolt Rally, and, since 2007, at the James Theatre, the annual Dungog Film Festival.

The bicentennial celebrations of Australia in 1988 with its accompanying funding for historical publications and other markers resulted in a series of books and memorials including the stones in Jubilee Park at Dungog, and the book Centenary of Memories, a collection of articles over 100 years from the Dungog Chronicle, which, by co-incidence, had begun publication in 1888.

Heritage Survivals

-

Honour boards

-

Dave Sands Memorial

-

War memorials

-

Foundation stones

-

School and Church Centenary books

2 Maitland Mercury, 17/1/1861, p.3. Presumably this was a paper balloon with an attached candle providing the hot air to lift it as is common is China today.

9 See also Defence.