teaching and learning by children and adults

- Early schools – National/Denominational then Public

- Dungog Public School

- Clarence Town Public School

- One-teacher schools

- Glen William

- Other schools

- School closures

- Catholic Schools

- Higher Education

- Sunday Schools & Scripture Classes

- Adult Education

- Other aspects of education

Education within the Williams Valley has taken a path determined in the main by Colonial and State Government policies. In the first European generation education was taken up by private schools often associated with churches, although attended by children of mixed denominational backgrounds. Thereafter, the National and then Public School system provided most education with a Catholic system paralleling this. At first these schools were established within reach of pupils, making the majority of schools small, one-teacher affairs. Gradually a combination of improved transport and falling numbers led to a concentration of educational resources into fewer but larger schools and the transporting of pupils over longer distances. Higher education was for long undertaken outside the Williams River area or by correspondence, until a Central School and then a High School were established at Dungog.

Adult education has been limited or non-existent until community education began in the 1980s, while in recent times an increasing number of families have taken up home schooling.

Early schools – National/Denominational then Public top

Before the establishment in 1849 by the Colonial government of the Irish National Schools, education within the Williams Valley and nearby districts was in the hands of private schools.[1] These were sometimes sponsored by a large estate owner to cater for the children of tenants or were Church based, with the Colonial government from the 1830s providing some subsidies on a denominational basis. Such private schools included what may have been the earliest educational facility within the three valleys, that at Tillimby estate near Paterson, where there was a ‘church-cum-schoolhouse’; then Lowe’s at Clarence Town (1834-47), and that on the Cory property at Vacy (1850). In the 1840s a number of schools are recorded at Dungog with some teachers described as ‘British and Foreign’, which may imply the scripture based teaching they used and/or that the source of their funding was the British and Foreign School Society.[2] There were also schools at Allynbrook and Paterson (1839), Bandon Grove (1850) and a Church of England school at Dungog operating from at least 1858.[3] These schools, however, never catered for more than a small proportion of the children of the district.

In 1849, the government established a dual system of education with National and Denominational schools; both subsidised by government funds. Local communities could make applications and, if approved, the Board of Education would provide two-thirds of the costs plus a salary for a teacher whose income would be supplemented by individual school fees. The Board’s contribution was set at £40 and for this, plus what they could collect in fees, a teacher was to be:

imbued with a spirit of peace, of obedience to the law, and loyalty to the sovereign, and should not only possess the art of communicating knowledge, but be capable of moulding the mind of youth, and of giving the power which education confers a useful direction.3

The first National School was that at Clarence Town (1849), making it one of the oldest government schools in NSW; after this came, among others, Brookfield (1851), Dungog (1851), Vacy (1859), and Bandon Grove (1862). After 1866, the Public Schools Act lowered the minimum number of children required and so more schools were established, such as Eccleston (1867), Gresford (1868), Allynbrook (1869), Mount Rivers (1875), Paterson (1875), Lostock (1878), and Martins Creek (1892).4

The number of Denominational Schools is less clear; three Church of England Schools are reported in 1848 at Dungog, Paterson and Lostock, and six Presbyterian local School Boards are reported in 1849 – Clarence Town, Brookfield, Vacy, Dungog, Paterson and Gresford.5 A Wesleyan School in 1850 is also recorded on the Tillimby estate near Paterson.6 The Presbyterian Church at this time aimed at providing a ‘secular’ education, choosing to use the same books as the Irish National Board. Though at Paterson, the Presbyterian School also advertised that: ‘Preference will be given to one who can speak and teach the Gaelic language grammatically’.7 Schools set up by the Church of England used the books of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and the Wesleyans and Catholics used books of their own choosing.8

Many of these early Presbyterian Schools were happy to convert themselves into National Schools once the opportunity arose and this happened at Dungog town itself, while at Gresford and elsewhere it was a Church of England school that converted, though usually after a longer period.9 The Church of England school at Paterson, for example, which reputedly had only 38 out of 90 to 100 potential students attending it in the 1860s, was strongly supported by its minister even after the Board of Education had withdrawn its certification.10

Dungog Public School top

At Dungog village in 1849, some 153 children were reported as justification for establishing a ‘National School’.11 At this time it was proposed to merge the Presbyterian school into a National School in the same building, on the corner of Windeyer and Chapman St, and with the same teacher, Joseph Ross. The school had opened by 1851, but Joseph Ross resigned in 1852, declaring that the £40 salary was insufficient. After a further turnover of teachers, a Mr and Mrs Gibbs, who had been running a private school, took over. Enrolments rose from an initial 26 to 84 in 1852 when the school unexpectedly had to close due to Mr Gibbs being ‘in the lock up and can’t get bail’.12

In the following years, the resources available to the schools of the Paterson and Williams River school districts seem to have been limited according to both an Education Commission report and a detailed complaint from a Dungog correspondent.13 It was not until the mid-1860s that the school at Dungog received a purpose-built building. In 1863, a new committee, comprising George Mackay, Joseph Fitzgerald, Robert Alison and Thomas Abbott, was formed to erect a new school building, which opened in January 1865 after the school committee raised some £323 to build on what was probably the site of the old court house, and after having the old cell blocks demolished.14

Soon after this, the Public Schools Act of 1866 transformed the National schools into the now familiar Public Schools.15 In 1867, the Local School Board consisted of George Mackay, Robert Alison and Dr McKinlay.16 This committee established the fees at 6d per week for the first child and 5d per week for each subsequent child. The Church of England school at this time had 51 pupils and perhaps somewhat lower fees. In the following years, money was raised for the teacher’s residence and expansion required for the separate scripture classes, as required by the Education Act.

When the Church of England school closed in 1881, room was needed for the influx of new pupils and it was reported that some families were unable to send their children due to lack of room.17 In the 1880s, more land was resumed, pupil teachers and assistant teachers appointed, and in 1889 a request that the school be designated a ‘Superior School’ was granted.

The number of children requiring education continued to grow as the population grew and, in 1891, the Minister visited the school. In 1893, some £700 for a new teacher’s residence was acquired, further land was resumed and application made in 1897 for an evening school for older students, but this does not seem to have been a success. In 1910, further expansion took place in anticipation of a rapid population increase with the opening of the new railway line, with the school inspector waxing lyrical and reporting that ‘Dungog must shortly become a great Railway Centre’. At a cost of £1,709, four new classrooms and a hat room were built in 1910 and, in 1913 some 225 pupils were being taught by a headmaster and four assistants. In 1917, electric lighting was available, though only in one classroom; a kindergarten was begun in 1929 and, in 1935, pupil numbers reached 300. The following year the footpath was laid down outside the school and more land resumed.18

Clarence Town Public School top

A private school organised by the shipbuilder William Lowe is reported to have taught at least the children of his employees from 1834 to 1847. Lowe was among those who signed the deeds for the land on which the new National School was established in 1849. Lowe also provided a temporary building while the new school and teacher’s residence was under construction; this was completed by 1851.19

The first examination in 1852 of the school was a public affair at which all were pleased with the quality of both the teachers and students:

On the 21st instant our village of Clarence Town presented for once quite a holiday scene, in consequence of the examination of our school. Parents, children, local patrons, and others from a distance, crowded our substantial, commodious, and neatly-furnished school-room to excess. Since the opening of our National School we have been favored with most efficient teachers; first Mr. and Mrs. Kirk, and now their worthy successors, Mr. and Mrs. Gardner, all trained in the Normal School in Sydney; and the advanced state of the children on examination day certainly proved that not only is the system good, but that here it has been well worked.20

By 1854, the attendance at the school is reported to have been at least 80, ‘although it was a Friday’.21 In the 1860s, a Catholic School was established at Clarence Town and, in the 1870s, this led to some competition for student numbers as after the 1866 Act the Catholic School depended on maintaining a minimum of 30 pupils to receive its government subsidy. At one point, the then Council of Education insisted both schools charge the same – 6d for the first child, scaling down after that until the fifth and more were free – as the cheaper Catholic School was felt to be poaching Public School students. In 1874, this Catholic School closed when its government subsidy was removed.22

In 1866, a part of the school grounds was sold off to provide money for extensions to the school.23 However, by 1876 a new building and residence was built, which although bigger, proved to be too small by 1886 when enrollment reached 153.24

One-teacher schools top

Small schools were established in many of the farming communities around the three valleys as intensive land use, particularly after the growth of dairy farming, meant high numbers of families, while the impossibility of travelling to the larger centres for schooling required that schools be nearby. In the Williams Valley: Salisbury, Bendolba, Munni, Underbank, Bandon Grove, Glen Martin plus Catholic Schools at Brookfield, Clarence Town and Dungog were established. While on the Paterson and Allyn Rivers, there were schools at Eccleston, Allynbrook, Mount Rivers, Lostock, Gresford and Paterson. In 1868, the Church of England schools at Gresford, Upper Bendolba and Clarence Town lost their Denominational Board support due to falling numbers – the minimum was 30 students.25

As population grew, more schools were opened, with, in 1879, a number of new Public Schools opening or upgrading from Provisional status, including Caergurle (Allynbrook), Gresford, and Welshman’s Creek. Half-time schools at Little River and Munni were already operating at this time.26

While the history of the many individual schools might appear similar, in fact they are sufficiently diverse to each contribute to our understanding of how these tiny institutions of education worked within the isolated communities they served.

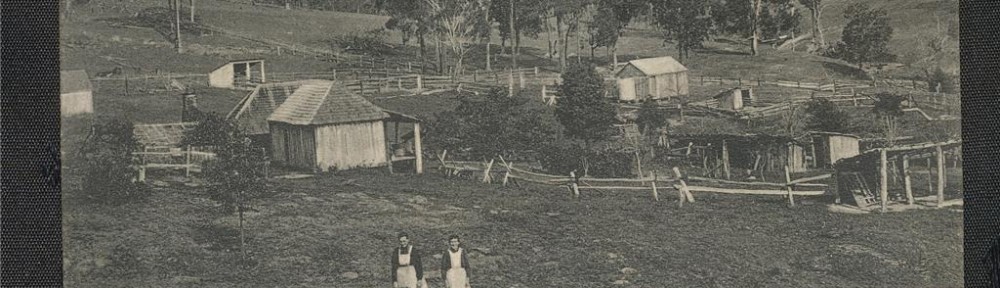

Glen William top

Glen William was a heavily tenanted district just up river from the head of navigation at Clarence Town. The community applied for and was granted a school license to be situated on two acres given by local landowner Thomas Holmes. The petition claimed 119 school-aged children in the area – 40 Anglicans, 32 Presbyterians and 47 Catholics. To accommodate these children a building for £120 was proposed, one-third to be raised locally. The plan was unusual in that the teacher residence was placed in the middle with boys’ and girls’ classrooms on either side, although there is no record that such a design was ever implemented. A building was eventually constructed, however, after many contractual delays which saw teaching out of the half finished building for a time.27

The obvious problem with a system that relied on fees to supplement a teacher’s salary was that smaller schools in poorer areas would always be unable to offer as much. The first teacher at Glen William, for example, received only one penny per student per week and considered the food situation forced him into vegetarianism. In 1864, this fee was 3½d per student. Teacher quality was low and this arrangement ensured only those unable to get better positions would apply to small schools. Another aspect of this school was the overbearing attitude of the local landowner – Thomas Holmes – with many parents also his tenants, a feature of numerous teachers’ complaints at Glen William.28

By 1851, the school at Glen William had 74 children, the highest number it ever had. In 1852, a report on the school at Glen William noted: ‘Spelling bad, seemingly from vicious pronunciation learnt at home.’ By 1859, attendance had dropped so much that the school was closed, to be re-opened only when parents guaranteed an attendance of 48. Many things kept children away from school, such as the need to help on the farm, poor roads, and flooded creeks.29

A tenant farmer in 1880 was reported to be paying £25 per year for 14 acres, and such high rents, as well as floods and poor crops drove many out of the district. This and sub-divisions of the larger estates led to a drop in tenants and, therefore in numbers of children so that by 1873 the two Public Schools at Brookfield and Glen William both became half-time schools, meaning they shared a teacher, who had to walk the three miles between them each day to teach at both.30

Teacher quality could be low and methods various. Samuel Rutter at Glen William, for example, was an ex-seaman who felt learning by rote had greatly damaged the children’s education. Opposition from parents, however, greatly soured his efforts. In addition, teachers’ wives were generally expected to teach such subjects as sewing to female students (for no extra pay of course), as the wife of Glen William’s first teacher did.31

In 1890, the school at Glen William burnt down, supposedly caused by parents living across the flood prone river at Banfield who felt aggrieved at being refused their own school – though there was a private school catering to 16 children in Banfield at this time. Previous to this, a dispute about the location of a footbridge to assist children’s access to the school had involved the teacher and inflamed tempers. Later, the Banfield people accused the teacher of ‘incompetence, cruelty and intemperance’, but this was dismissed. A bridge was finally built in 1895 for £800 with disputes over the location leading to delays.32

Lessons in the 1890s involved anatomy, geography, history and grammar. The history was English but did include the discovery of Australia, while the geography was also European. One teacher, Hugh Jones, introduced agriculture into the teaching at Glen William in 1897. Ahead of his time, this subject was not officially introduced until 1902. The Glen William school opened its library in 1899, doing so with a picnic attended by 300 people. The library consisted of 132 volumes in a ‘substantial case with glass doors’.33

The years saw many changes in this small school. The introduction of motor vehicles led to many students arriving by milk carrier, which was often late and meant many also needed to leave early. A bus service was not established until the mid-1950s. A tuck shop was established in 1970, in 1986 the first computer arrived, and in 1994 the first female teacher.34 This school continues to operate.

Other schools top

The public school established at Bandon Grove in 1862 had, like many, been preceded by another, probably denomination, school. In that year, an inventory of the school included two maps of the world, two of Australia and one each of Scotland and England. For the teacher travelling to Bandon Grove, the cost was £2/10 from Sydney to Clarence Town, then a further £2 to Bandon Grove, plus £1/10 for lodging and meals on the trip; a total cost to the Board of Education of £6.35

In 1875, a new school opened at Salisbury where it was reported that, ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’ was regularly played on the gramophone.36 Empire Day (May 24th) was a big event with a school picnic in Jim Rumbel’s paddock and a dance that night in a shed.37 The Salisbury School enrolment was: 1928 = 13, 1934 = 16, 1957 = 24.38 Broken down, the Salisbury School roll in 1957 was: K = 1, 1st = 2, 2nd = 2, 3rd = 8, 4th = 1, 5th = 4, 6th = 6, and of the 24 students 5 were from the Rumbel family.39

A school whose numbers fell would become provisional, then subsidised. Those that fell below this level could in fact still operate in a sense. This happened to Binglebrah school established in 1878, it managed with a very high turnover of teachers until 1889 when falling student numbers reduced its status to ‘house-to-house’. Under this system ‘teaching stations’, which might be homes, were visited on a regular basis by a teacher covering a number of such stations. Binglebrah dropped to this status twice (though only for a short period each time), as well as periods as a half-time school. This school finally closed in 1933.40

School closures top

By the 1950s single teacher schools were closing as student numbers dwindled as the number of dairying families declined, families also became smaller, and students could take the increasing number of subsidised buses. The last of the small schools had closed by the 1980s and the only Public Schools now operating in the Williams Valley are those in the two towns plus Glen William. A crucial element allowing these school closures was the Education Department subsidy to local bus operators.

Catholic Schools top

With the 1866 Public Schools Act, and compulsory education in 1880, the previously loose system of Public and Denominational schools was gradually tightened with greater government oversight of Denominational Schools. It was this rise of the so-called ‘State schools’ that was met with great fear by the Catholic Church in Australia. The hostility of the Irish to a largely ‘English’ government and of the Catholic clergy to potential contamination, resulted in a huge effort to establish a separate school system on the part of largely poorer parents, greatly assisted by a plentiful supply of teachers in the form of Irish clergy.

The Bishop of Maitland caused a public stir in 1870 with his efforts to ensure that Catholic children were withdrawn from the Glen William Public School and sent to the Catholic School at Clarence Town.41 Despite his efforts, this Clarence Town School closed in 1874. Another Catholic School was established at Brookfield, though not until 1892; running until 1958.42

In 1888, a Catholic school was established at Dungog with nuns from the rapidly expanding Sisters of St Joseph, who had began in the Hunter Valley with only four nuns at Lochinvar in 1883.43 The three nuns, aged from 22 to 27, first occupied a house in Dowling Street and, soon after, in 1889, a school opened in a room within this cottage. The present Convent was built in 1891 and the nuns moved in early the following year.44 The school also moved to the new location and reportedly had nearly 100 pupils, more than half of whom were non-Catholics.45 With numerous bazaars raising funds, a separate school room was built in 1913 for £700.46 Additions to the school were built in 1923, 1952, 1976 and, most recently 2002. The 1976 addition was in fact the Brookfield School transported to the site after that school’s closure, to become ‘Brookfield House’ and allowing the former Infants Block to be converted into the ‘Father Bourke Memorial Library’ – Father Bourke having served over 55 years as parish priest of Dungog.

The Sisters of St Joseph taught at the Dungog Catholic school until 1986 when it continued with lay teachers only. A small community of nuns continued to reside in Dungog, however, providing a range of community support activities until their final departure in early 2000.47

While in general the Catholic community was successful in establishing its own education system, there were cases of Catholic Schools failing. The case of the Clarence Town Catholic School gives us an indication of how this struggle took place. First established the 1860s, the Clarence Town Catholic School, after the 1866 Public Education Act, needed a minimum of 30 pupils to continue with its government subsidy. It was having trouble getting these numbers and, in the 1870s, was happy to take pupils from the Clarence Town Public School – which it was partly able to do by charging a lower fee. One parent was accused of having ‘sold his child to the Pope for 3d a week’. The Council of Education solution to this was to make both schools charge the same fees. Unable to achieve its minimum numbers, this Catholic School closed in 1874 when its government subsidy was removed.48

Higher Education top

In theory, most pupils left their various schools at age 14, and the Williams Valley district did not receive any secondary education until the 1950s. In practice, with the support of the teacher, it was possible for some to receive higher education, even as early as the 1880s. Elizabeth Skillen recalled that a group of sixteen and seventeen year olds stayed on at Dungog Public School to learn at high school standard and that at least one student passed the university entrance examination.49

Higher education was provided in a number of ways. Sometimes a student would simply stay on for an extra year or two. In 1884, Maitland Girls’ and Maitland Boys’ High Schools were established, but transport costs and high fees made this an unlikely choice for most in the district.50 Those who could afford it would send their children to boarding schools, and, once the railway made it possible after 1911, many more made the regular journey to Maitland schools, either every day or staying in Maitland for the week and returning home on weekends. Trains known as School Trains did the run with separate carriages for boy and girl students. The entrance exams for these schools, including scholarships, were held at Dungog and other locations.51

By 1938, some 106 students travelled each day or boarded in Maitland or Newcastle at various Secondary Schools, while a further 15 in Dungog and another 11 in smaller district schools studied what were called ‘leaflet’ or correspondence courses. In the 1950s, Marie Nicholson became the first Dungog School student to attain the Intermediate Certificate. She achieved this through a mixture of correspondence courses at her home and attending school in Salisbury and in Dungog. This achievement led to one of the Dungog Public School houses being named Nicholson.52

By 1950, agitation began for the establishment of secondary education and a Central School was established in Dungog.53 Students from further up the Williams Valley went in the mornings with the Shelton’s mail run, and in the afternoons Harry Shelton returned them using an 8 seater car; later this was a bus, as the numbers seeking higher education grew. In 1951 this trip took three students, two from Salisbury and one from Dusodie, including Marie Nicholson.54 Finally, in 1971 Dungog High School opened, the only High School within the Williams Valley of nearby districts.

An interesting, if short lived, addition to higher education was Durham College established in Dungog by H S Crowther as a private boarding school that at one time had 30 boys attending it. Set up in an existing house, an L-shaped schoolroom, dining and dormitory building was erected in 1907, separate but close to the main house. Henry Stewart Crowther, M.A., Oxon., (Late Exhibitioner of King’s School, Canterbury, and of Keble College, Oxford; 4 years Senior Assistant Master at Bilton, Rugby, and 3½ years at Cumloden, Melbourne), and also one time manager of Thalaba Estate, was head of this school which prepared pupils for matriculation and other examinations. In 1909, it was reported that this was the only college in NSW at the time with its own horse troop, and many who attended would have been of an age to participate in the First World War. Certainly obituaries of some killed in this war from as far as Gloucester mention attendance at this college. Durham College was well attended but the arrival of the railway was perhaps the cause of its early closure. It is not certain when the school closed, but by 1923 the house had become a private maternity hospital.55

Sunday Schools & Scripture Classes top

While the Church of England failed to establish a viable school system on the Catholic scale, it put its energy into Sunday Schools and, by 1868, Sunday Schools had been established at Dungog, Bendolba and Clarence Town.56 The Presbyterians at Clarence Town also had a Sunday School operating as early as 1855.57

This supplement to the perceived secularism of the Public School system was not enough for many however, and by the 1870s a movement began called ‘Bible Combination’.58 This meant a combination of Christians to get the Bible used in Public Schools. The movement professed a willingness to allow Catholics to use their version of the Bible, but never succeeded in allaying Catholic fears.59 In the 1870s, for example, a teacher was required to sign an agreement stating: ‘I shall abstain from giving special religious instruction’ – ‘special’ in this case meaning specific denominational instruction as readings from ‘scripture’ were in fact often part of the supplied texts.60 Eventually, this movement did establish scripture classes within Public Schools. Scripture classes began in 1916 at Glen William, for example, resulting in many of the Catholic students being granted extra free time to play.61

Adult Education top

These early schools were designed to provide basic education up to the early teens or a little beyond, at most. The need to provide educational opportunities for older people was, however, recognised and the School of Arts movement became widespread. However, in Dungog, as in most towns, the educated middle class dominated, and these Schools of Arts were rarely places of education beyond the provision of a library, with very often billiard rooms taking up more space. Some individual efforts were made to provide classes for young men on occasion, such as the evening school for young men in the Paterson River operated by Summer Hill Public School teacher Maurice Collins in 1894.62

Since the 1980s and the growth of community centres and community workers, many adult education programs have been promoted. These often focus on crafts and the learning of particular skills, but numeracy and literacy skills, as well as general vocational courses have also played a role. Since 1985 the Tocal Field Days, initially aimed at the many newer residents striving for a rural lifestyle on small acreages, have been another aspect of adult education. In 2012 the Dungog Community Centre re-established adult education classes within the three valleys.

Other aspects of education top

Local teachers early formed the ‘Williams’ River Teachers’ Association’. This was not a trade union but an association ‘for mutual improvement, and the discussion of educational topics’. Not only teachers from the Public Schools at Clarence Town and Dungog joined but at least one teacher from a denomination school, Mr. J. P. Collier, of the ‘Cert. Den. C. E. school, Bendolba’ also attended. Meetings were to be ‘on the first Saturday each month, at eleven a.m.’63 There are also references to both a Dungog Teachers’ Kendall Literary Association in 1903, and a Dungog Teachers’ Association in 1906. These may have been the same group, with the latter recorded as having monthly meetings, including one in 1909 when Mr Dart, Inspector of Schools, gave a presentation on the Montessori method along with permission to try this method ‘one hour weekly’.64

As far as teachers were concerned, Dungog seems to have been the most central location such as when regular teachers’ examinations were held:

The half-yearly examination of school teachers of the district has just been completed, under the supervision of Inspector M’Lelland. A goodly number presented themselves, and among them a few for the pupil teachers’ grade. The holding of the examination in Dungog the last three times has proved a great convenience to teachers of the district, who formerly had to travel to Maitland, which entailed considerable expense.65

Another aspect of the changing school system has been the decline in the role of the P&C. Parents & Citizens Associations began as early as 1905, though most schools established them later. Organising fundraising for extra equipment and special events such as Empire Day or Christmas Picnics were part of the role of these P&Cs. Community support was for many years essential to the establishment and running of schools, and, for a time, significant in the running of the High School also. However, as teachers have grown more professional and no longer isolated in single teacher schools, this community element has gradually declined.

From perhaps the 1920s through to the 1970s, inter-school sports competitions were popular, with schools of various districts coming together to participate.66 In the 1950s and 1960s, it was common for the district schools to hold a combined Sports Carnival with marches down the streets of Dungog. From perhaps 1957, a Triangular Sporting Event was held in rotation between Dungog, Gloucester and Wingham until the 1960s. A final triangular was held in 1970 between Dungog, Bulahdelah and Nelson Bay.67

At various times schools have also introduced innovative or vocational courses, such as classes in ‘Dairying’ (including butter and cheese making), at Dungog Public School.68 Also, the Gould League of Bird Lovers was established at Glen William Public School around 1926.69 School uniforms have made a compulsory appearance since the 1950s (but never in the single teacher schools), though differing shoes began to appear in 1980s, and, in the 1990s, girls were allowed to wear shorts while the tie disappeared.70 Corporal punishment has also disappeared entirely.71

In more recent times private organisations have been set up to provide education on the environment or opportunities for personal development. Taking advantage of the increased mobility of even school children, these organisations are able to cater for schools on a regional basis and are attended by students from well beyond the boundaries of the Williams Valley. Wangat Lodge on the upper Williams River and Riverwood Downs on the Karuah River, are two examples of this education type. Wangat Lodge was set up as a wildlife refuge in 1985 and after 1988 began to develop school programs under which some 20-30 school groups a year are given environmental education.

A final element in the history of education in the Williams River has been the gradual growth of home schooling. This is an educational option arising not from established families, but one brought into the district by families striving to escape urban environments and provide for their children in ways organised schooling cannot. There are an estimated 10 families within the Williams Valley who home school.

Heritage Survivals

-

Former Durham College school and dorms

-

Individual school histories

-

Former school residences and schoolrooms