the provision of types of accommodation

The initial provision of accommodation for the first settlers in the Williams Valley was very much along class lines, or certainly that of occupation, which amounted to the same thing. Convict shepherds were provided with the most basic, slab huts, or, if on a large estate, perhaps a brick-built barracks such as that at Tocal. Landowners provided themselves with modest cottages and houses at first, but these were replaced as soon as resources allowed with grander homes. Tenants and small freeholders built a variety of modest cottages in wood.

Of this variety of first generation settler accommodation, very little remains. Charles Boydell on the Allyn River has left us an impression of his French doors and the remaining outbuildings of Duncan MacKay’s Melbee near Dungog are impressive.1 In the next wave of building, those who could afford to do so began to build more substantial homes such as those at Rocky Hill in stone and brick above the Williams River, at Duninald on the Paterson River, and on the estates at Tocal, Gostwyck and Trevallyn.

An early description of the accommodation on a sizeable 854 acre property on the Allyn River for sale in 1855, including separate accommodation for servants, is:

A weatherboarded COTTAGE with verandah, containing seven rooms, viz.:

Two apartments, 18 feet square

One ditto, 12 feet by 18 feet

Four ditto, 10 feet square

Kitchen detached

Two Cottages composed of slabs, shingle roofs, each containing three rooms, being farm servants’ apartments.2

On the Williams River a generation later in the 1880s, the Lean family was able to build Figtree House, ‘a brick cottage containing nine rooms with a large cellar …’3 And a generation on again, when Ernest Guy Hooke renovated the imposing Rocky Hill, he added a windmill to lift the tank water, an air gas plant, and sewerage to make it ‘one of the most up-to-date residences’.4

An aspect of accommodation was that buildings and materials were used and re-used throughout this time, and is summed up in a story told at a Golden Wedding Anniversary. The teller related of a house in Brookfield where his parents lived that had been built by his father as a public house; it later became a private dwelling with a large room used as a school, dances and Masses. Finally, the house was demolished and the bricks used to build Brookfield Convent. The teller concluded by saying he was born in the old house, went to school in it, danced in it, went to Church in it and his daughter, a sister of Sister Joseph, taught in it.5

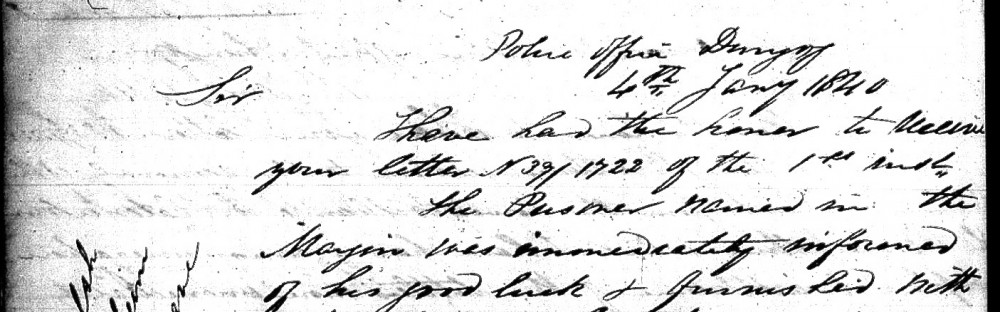

An interesting sub-set of the grand homesteads of the larger landowners such as Dingadee and Cangon, was the town house of the bank manager. Bank managers were at first always resident and the banks designed these houses to raise the prestige of both their banks and their managers. Notable examples of this type of housing are to be found at Paterson, Dungog and even one from the 1960s at Gresford. That of the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney in Dungog was built in 1884 and designed by J W Pender of Maitland.

Overall, the design is a mixture of grandeur and restraint. The walls are built in triple brick, the facade is finished with fine tuckpointing, while inside, all window sashes and framework are in local cedar. Even the skirting boards are a study in calculated expense and display. The narrowest skirting is in the kitchen and other servant areas, with wider and more finished skirting in the bedrooms and other private areas. But the widest and grandest of skirting was laid down in the hallway, stairs and grand sitting room upstairs – areas visitors, including wealthy clients of the bank, would see.6

In addition to private accommodation, hotels and inns were also built to provide accommodation for travellers. Of these Stephenson’s Inn of Dungog is the only remaining from the earliest period and none are thought to have been any more substantial. Another, perhaps nearly as old and also in Dungog, was Sheridan’s, described as a weatherboard hotel with three parlours, a dining room, grooms’ and servants’ rooms, two sitting rooms, and seven bedrooms.7

A visitor in 1888 described several of Dungog’s Inns of that time. The Royal was a ‘large and commodious house’, while Sheridan’s had an ‘excellent reputation for sale of good stuff’, and the Settlers Arms was ‘a quaint but cosy inn and reminds one much of the country hostelries in England’.8 Both the Royal and the Settlers Arms continue to operate under those names today. The Royal was completely rebuilt as a 1940s hotel, while the Settlers Arms underwent major renovations around 1900.

Boarding houses provided another style of accommodation which gave women and children a place to stay who otherwise found the hotels unsuitable. Such boarding houses also provided for school teachers, bank clerks and other workers who might find themselves transferred into the Williams Valley.

During the building of the North Coast Railway line, large numbers of navvies such as the 150 men working on the Stroud tunnel in 1912, were provided with temporary accommodation of which an interesting description exists:

About the hills are the huts of the men built of timber of the small ironbark variety. The huts are made in a different manner to those of the North Coast huts built on works of a public nature. A frame is erected of sawn timber and covered in Hessian, which is coated with about three-eighths of an inch of cement.9

A range of accommodation types specific to various professions has also existed. The many simple timber cutters’ huts associated with bush mills and sleeper cutters’ camps are perhaps the direct descendent of the slab huts of convict shepherds. During the first half of the 20th century at least, it was common for single men to reside in ‘huts’ on properties the owners did not live on. These men would manage eucalyptus regrowth, control for rabbits and provide general security. Little is known about these men or their huts, but an analysis of the Webber’s Creek catchment area has come up with a total of 11 huts and houses in this one locality.10

Another accommodation type was teachers’ quarters, often provided as part of the school building itself.11 Perhaps unique within the Williams Valley district, until the establishment of Tocal Agricultural College in the 1960s, is the students’ accommodation built as part of Durham College in Dungog. Finally, a railway barracks was provided for train crews at Dungog until the 1960s.

The nature of travellers’ accommodation changed as the bulk of travellers switched from those on business, such as commercial travellers, to those seeking to enjoy themselves by travelling. As a result, guest houses associated with the Barrington Tops became popular, especially, for many years, the Barrington Guest House, originally built by the owner of the Royal Hotel, Dungog. Built in 1930 and large for a guest house, it could accommodate more than 50 people. The Barrington Guest House continued to offer ‘guest house’ style (shared bathrooms, trivia nights, and communal meals), until well into the 1980s, and people continued to come to the Dungog area solely to visit the Barrington Guest House right up until its destruction by fire in 2006. Even today, many visitors to the Dungog area request information about the Barrington Guest House and are disappointed to learn it no longer exists.

In more recent times travellers have been serviced by caravan parks, motels and bed & breakfast style accommodation, all based on the flexibility allowed by the car. In addition, two alternative accommodation types outside this range have been established within the Williams Valley. These are Wangat Lodge, which provides basic accommodation, and the semi-luxurious self-contained accommodation of the Barrington Retreat, also at Wangat, and Eaglereach Wilderness Resort at Vacy. Wangat Lodge was established in 1985 as a combined educational and recreational facility and caters for day-trips for schools groups as well as overnight accommodation for groups and individuals. The emphasis is on the environment, many of the buildings are of mud-brick, there are no televisions, and guided tours of the surrounding environment are offered.12

Billed as eco-tourism, the Eaglereach Wilderness Resort and Barrington Retreat facilities utilise community title to establish numerous privately owned accommodation units within a managed resort. Located on top of Mt George, the Eaglereach area had seen limited human intervention due to its steepness, while the Barrington Retreat was located in former dairying country with much regrowth. Both resorts feature high-end accommodation and are designed to attract urban dwellers who wish uncomplicated access to a bush environment.13

A limited amount of public housing has been erected in Dungog in the 1950s and since been sold privately. At Main Creek, a hotel for rehabilitation patients was established until its destruction by a fire in the 1970s which killed many of its residents. Of more long-term impact upon the community have been changes in the way the aged are catered for, resulting in the development of a great deal of aged-care accommodation, ranging from self-contained units of Alison Court and Ironwood at Dungog to the specialist nursing home facility of the community operated Dungog District Nursing Home.

6 Williams, Ah, Dungog, p.16.